Daniel O’Connell

Derrynane is the ancestral home of Daniel O’Connell (1775-1847), lawyer, politician and one of the most important figures in Irish history. He was named ‘The Liberator’ because of his successful campaign for equal rights for all Irish people. His ability to harness the support of ordinary people resulted in one of the first modern mass-democratic movements. He became known around the world and played a leading role in the international movement to abolish slavery.

O’Connell spent his childhood in Derrynane and returned here whenever he could. He inherited the house in 1825 and his time in Derrynane was one of the chief joys of his life.

“This is the wildest and most stupendous scenery of nature – and I enjoy residence here with the most exquisite relish… I am in truth fascinated by this spot: and did not my duty call me elsewhere, I should bury myself alive here.”

– Daniel O’Connell, 22 October 1829

In 1790, Daniel and Maurice were sent to school at St Omer in France and, subsequently, to the English College at Douai. These turbulent and blood-thirsty days of the French Revolution sowed within Daniel a dislike of republicanism and a realisation that the nonviolent, constitutional path was the best means of bringing about political change. Pursuing a career in law, Daniel was called to the Irish Bar on 12th April 1798. As a barrister, he had the reputation of being able to win even the most hopeless cases and became known as ‘the Counsellor’.

Although O’Connell’s political career had started in 1800, in opposition to the Act of Union between Britain and Ireland, his first political campaign was for Catholic emancipation. He formed the Catholic Association in 1823, a mass movement agitating for the same political rights for Catholics as those enjoyed by Established Church members. In the 1826 General Election, pro-emancipation candidates won in nine counties. At an 1828 by-election in Clare, O’Connell himself was elected M.P., but could not take his seat because he was a Catholic. However, the political momentum generated forced the passage of the Emancipation Act of 1829. This earned O’Connell the name of ‘The Liberator’.

1843: The Year of Repeal

Once Daniel O’Connell won the right for Catholics to sit in the British House of Commons in 1829, he then dedicated himself to the repeal of the Act of Union and the re-establishment of an independent parliament for Ireland. After over a decade fighting for this cause as a Member of Parliament, he announced that ‘1843 is and shall be the great Repeal year’. He and his followers in the Repeal Association set about organising peaceful ‘monster meetings’ throughout the country to demonstrate the support for their cause and force the British government to grand their demands.

The ‘monster meetings’ attracted huge crowds – around one million people are said to have attended the meeting at the Hill of Tara, the ancient seat of Ireland’s high kings. O’Connell spoke at thirty-one of the meetings and travelled over 5,000 miles that year. The British government wanted to suppress the movement and banned a planned meeting in Clontarf outside Dublin on 8 October 1843. Although O’Connell cancelled the event to avoid any loss of life, he and some of the other leading ‘Repealers’ were arrested and charged with ‘seditious conspiracy’.

Imprisonment

O’Connell came here to Derrynane to rest and prepare for his trial which began in the Four Courts in Dublin on 15 January 1844. O’Connell defended himself; it was to be his last court case. He used the trial as a platform to argue for Repeal and criticise British rule in Ireland. O’Connell and his associates were found guilty. They were sentenced on 30 May to serve a year in Richmond Bridewell Penitentiary on the South Circular Road in Dublin.

O’Connell’s fellow prisoners included his son John O’Connell, Thomas Steele, Charles Gavan Duffy, Richard Barrett, John Gray, and T.M. Ray. They were very comfortably housed in the private quarters of the prison’s Governor and Deputy-Governor. The spacious rooms and gardens in which they spent their days were recorded in a series of paintings by the artist Henry J. O’Neill. They were allowed to employ servants and family members could stay with them also. A steady stream of gifts and guests flowed into the prison and, according to Charles Gavan Duffy, ‘the dinner-table was never set for less than thirty persons.’

Read More...

Visual evidence of O’Connell’s imprisonment in the Irish Arts Review, Summer 2014.

Release

O’Connell and the other prisoners were freed on 6 September 1844 after the British House of Lords overturned their convictions. However, they returned to Richmond Penitentiary the next day so a ceremonial release could be staged. O’Connell left the prison aboard a special triumphal chariot drawn by six grey horses. His grandchildren, dressed in green velvet costumes and white-feathered caps, sat on the bottom level of the chariot with a harpist above them playing Irish songs. O’Connell and his chaplain, Rev. Dr John Miley, rode on the top level and waved to the crowds.

Roughly 200,000 people lined the streets to cheer O’Connell. The procession did not go straight to his home on Merrion Square. Instead it deliberately passed by the Four Courts where O’Connell had been on trial and then travelled on to the gates of Dublin Castle, the seat of British government in Ireland. O’Connell also stopped and pointed at the old Parliament House on College Green, showing the crowd that his campaign for the repeal of the Act of Union would continue. Despite this large demonstration of popular support, it was to be his last great political triumph.

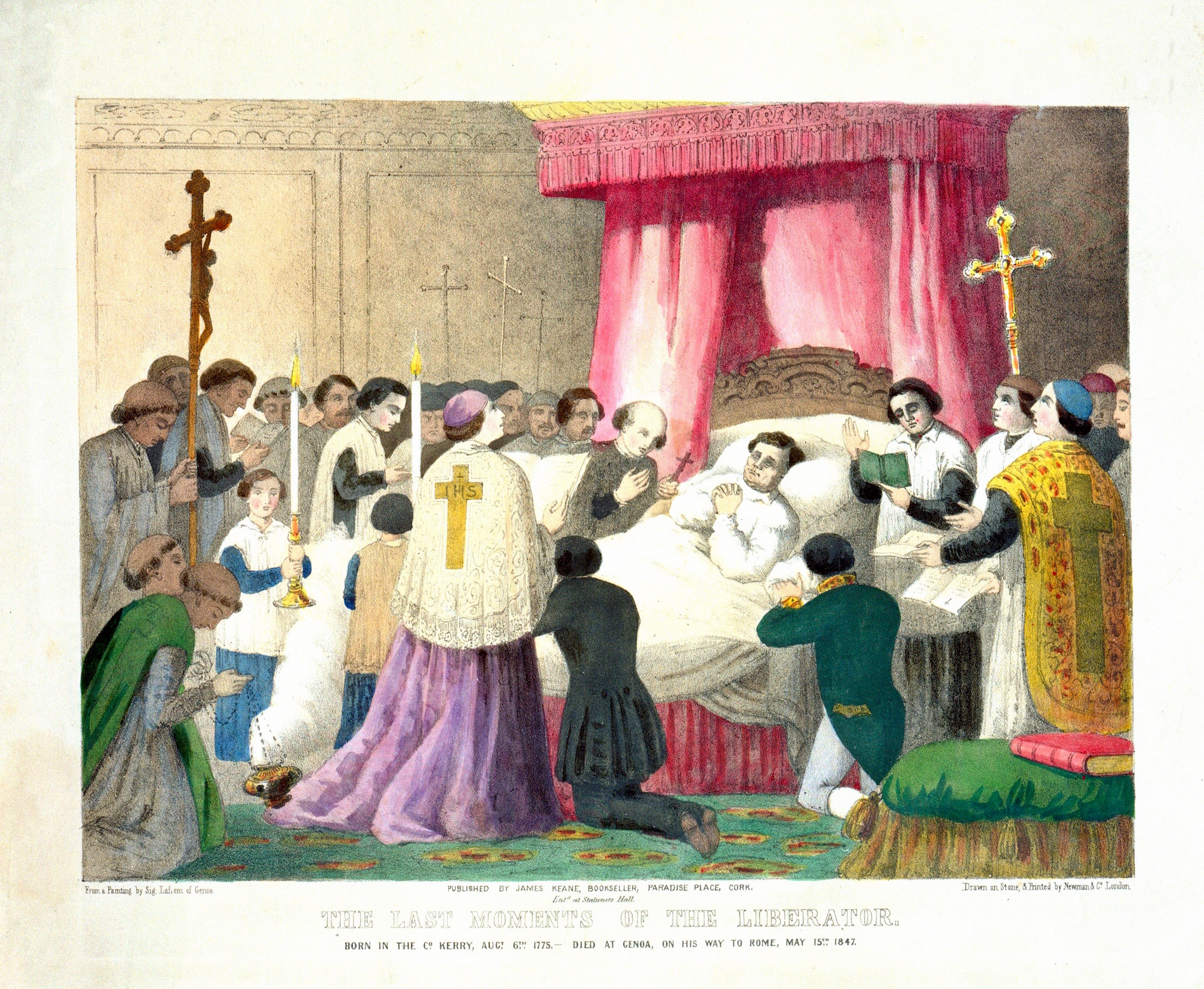

The Death of O’Connell

O’Connell’s last years were characterised by disappointment and division. His campaign to Repeal the Act of Union lost direction and his leadership was challenged by ‘Young Ireland’, a more radical group within the movement. The greatest blow was the devastation caused by the Great Famine. In 1847, with millions of his people facing starvation and death, O’Connell pleaded for help in the British House of Commons. Unfortunately, by that time his health was failing. His voice, which had once dominated enormous meetings and assemblies, could barely be heard.

O’Connell was facing death and in low spirits when he embarked upon a pilgrimage to Rome to receive a blessing from Pope Pius IX. His son, Daniel, his chaplain, Rev. Dr Miley, and a servant, John Duggan, accompanied him. O’Connell never reached his destination. He died in Genoa on 15 May 1847. His heart was interred in Rome but his body was returned to Ireland. On 5 August a huge funeral cortege passed through Dublin where thousands of people lined the streets to pay tribute to their dead leader.